The Journey to the West is the first romantic chapter-linked novel of divine and demonic themes in ancient Chinese literature. The earliest known version, Newly Engraved Official Edition of the Journey to the West with Illustrations from the Shidetang Publishing House in Jinling during the 20th year of the Wanli era (Ming Dynasty), did not attribute an author. Scholars such as Lu Xun and Dong Zuobin later confirmed Wu Cheng'en as the original author based on records from the Huai'an Prefecture Annals mentioning "Wu Cheng'en's The Journey to the West."

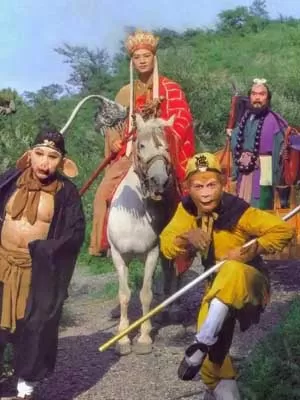

The novel primarily follows Sun Wukong’s birth, his training under Patriarch Subodhi, and his rebellion in Heaven. Afterward, he joins Zhu Bajie, Sha Seng, and the White Dragon Horse to escort the monk Tang Sanzang on a pilgrimage to India to retrieve Buddhist scriptures. Throughout their journey, the group faces perilous trials, subdues demons, and overcomes 81 tribulations before reaching the Great Thunderclap Monastery. There, they receive the Three Collections of True Scriptures from Buddha Tathagata, culminating in the five saints achieving enlightenment. Rooted in the historical event of Xuanzang’s pilgrimage, the story reflects Ming Dynasty society through the author’s artistic embellishments.

The Journey to the West is a masterpiece of Chinese mythological fiction, representing the pinnacle of ancient romantic epic literature. Alongside Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Water Margin, and Dream of the Red Chamber, it is hailed as one of China’s Four Great Classical Novels. Since its publication, it has been widely circulated in numerous editions, with six Ming Dynasty prints, seven Qing Dynasty editions and manuscripts, and 13 lost versions documented in historical records. After the Opium Wars, classical Chinese works began spreading to the West. The Journey to the West has since been translated into English, French, German, Italian, Spanish, sign language, Esperanto, Swahili, Russian, Czech, Romanian, Polish, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, and other languages, cementing its global influence.

The creation of The Journey to the West parallels that of Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Water Margin in undergoing a long process of accumulation and evolution. However, its developmental trajectory differs: while the former two blend historical facts with fictional expansion, presenting an illusion of "truth" to readers, The Journey to the West transforms a historical event through continuous mythologization and fantastical reimagining, ultimately presenting itself in a "mythical" form.

The pilgrimage of Xuanzang (602–664 CE) originated as a real historical event during the Tang Dynasty. In the third year of the Zhenguan era (629 CE), he departed Chang'an in pursuit of Buddhist truths, traversed over a hundred kingdoms, endured countless hardships, and finally reached India. After studying there for over two years, he earned acclaim as a keynote speaker at a major Buddhist doctrinal debate. Returning to Chang'an in 645 CE, he brought back 657 Buddhist scriptures. This extraordinary feat naturally sparked widespread imagination. Later, Xuanzang orally recounted his travels, which his disciple Bianji compiled into the twelve-volume Great Tang Records on the Western Regions. However, this work focused on the histories, geographies, and routes of the lands he visited, lacking narrative storytelling.

Subsequently, his disciples Huili and Yancong authored Biography of the Tripitaka Master of the Great Ci'en Temple in the Great Tang Dynasty. While praising their master and promoting Buddhist teachings, they interspersed fantastical tales with exaggerated, mythical flourishes, imbuing Xuanzang’s journey with a legendary aura. As these stories spread, they grew increasingly fantastical. Late Tang-era records like Accounts of the Extraordinary and New Tales of the Great Tang documented miraculous episodes from Xuanzang’s pilgrimage, cementing its place in Chinese folklore.

The Southern Song Dynasty storytelling script The Poetic Tale of the Great Tang Sanzang's Pilgrimage for Scriptures began weaving diverse myths into the pilgrimage narrative. It introduced the character of the Monkey Pilgrim, originally the "King of the Copper-Headed, Iron-Browed Macaques of the Purple Cloud Cave on the Mountain of Flowers and Fruits," who transformed into a white-robed scholar to escort Sanzang. Endowed with supernatural powers and cunning, he defeated the White Tiger Demon, subdued the Nine-Headed Dragon, and vanquished the Deep Sand God, ensuring the pilgrimage’s success. This marked the shift of the narrative’s central figure from Xuanzang to the Monkey King. The Monkey Pilgrim’s character drew inspiration from ancient Chinese tales of the strange, such as the white-ape spirits in Chronicles of Wu and Yue, In Search of the Supernatural, and Supplement to the Biography of the White Ape, while the rebellious, shape-shifting water demon Wuzhiqi from Ancient Chronicles of Sacred Peaks and Waterways particularly resembles the mythical Monkey King. The Deep Sand God in these tales evolved into Sha Seng (Sandy) in The Journey to the West, though Zhu Bajie (Pigsy) had yet to appear.

By the Yuan Dynasty, a more complete and vivid version titled The Story of the Journey to the West emerged, its plot closely resembling the final novel. By the late Yuan to early Ming periods, a fully fleshed-out version of The Journey to the West had already taken shape, laying the foundation for the timeless classic.

During Wu Cheng'en’s lifetime, Daoism had become a corrupt force, colluding with imperial rulers and losing its progressive significance as a grassroots spiritual tradition. By the mid-Ming Dynasty, Daoist priests had sunk into decadence and were widely despised by the populace. For instance, during the Jiajing era, the Daoist Tao Zhongwen was ennobled as Junior Guardian and Minister of Rites, currying imperial favor through healing, exorcisms, alchemy, and rituals. He conspired with the eunuch Cui Wen and the corrupt official Yan Song to manipulate power.

The Jiajing court also issued decrees promoting Daoism while suppressing Buddhism, confiscating assets from temples like Nengren Monastery, expelling statues of Sakyamuni from palaces, and later dismantling Buddhist shrines within the imperial complex. Simultaneously, the emperor ordered massive construction projects, such as the Sanqing Palace, and lavishly funded Daoist ritual ceremonies. These policies burdened the people with forced labor and drained the state treasury. Wu Cheng'en crafted The Journey to the West as a pointed satire of these abuses, using allegory to critique the era’s religious hypocrisy and political decay.

Long before Wu Cheng’en composed The Journey to the West, tales of the monk Sanzang’s pilgrimage had already circulated widely in folklore. However, Wu’s work was far from a mere compilation of these popular stories. He extensively reimagined and reshaped existing narratives. The Poetic Tale of the Great Tang Sanzang’s Pilgrimage for Scriptures, the earliest and most complete precursor to the novel, featured the Monkey Pilgrim as a white-robed scholar. Wu transformed this pious Buddhist figure—who aids the monk in seeking enlightenment—into Sun Wukong, a rebellious and fiercely independent character driven by passion and a thirst for freedom.

As one scholar noted, “Unfulfilled desires are the driving force behind fantasies; every fantasy embodies the realization of a wish, transforming an unsatisfying reality.” Wu Cheng’en infused The Journey to the West with two such unresolved yearnings: the longing for immortality and the pursuit of individual worth.

The novel’s opening chapters celebrate the birth of the Stone Monkey as a metaphor for new life. In Chapter Four, Sun Wukong’s dissatisfaction with the lowly title of “Keeper of the Heavenly Horses” and his eventual self-proclamation as the “Great Sage Equal to Heaven” reflect his struggle for recognition. Yet this title proves hollow—a placating gesture by the Jade Emperor to maintain celestial order. When excluded from the Peach Banquet, Sun Wukong realizes the deception and rebels against the heavens’ injustice. This arc mirrors Wu’s own frustrations with unrecognized talent during his early career.

Wu Cheng’en viewed death as a tragic inevitability, yearning instead for the immortality of deities who “share the lifespan of heaven and earth.” By his sixties or seventies, while writing the novel, he confronted his own aging—a stage paralleling Sun Wukong’s journey. Channeling a lifetime of disillusionment into the character, Wu sent the Monkey King across mountains and seas, enduring trials to seek the elixir of eternal life. Through this quest, the author transformed personal existential dread into a timeless myth of resistance and transcendence.

The celestial bureaucracy depicted in the novel—represented by the Jade Emperor’s court, the Underworld, and the Western Paradise—mirrors human governance not only in its administrative structure but also in its moral decay. These divine institutions are rife with incompetence and corruption. The chaos incited by Sun Wukong exposes the celestial regime’s fragility: the Jade Emperor’s inability to discern merit, the celestial generals’ cowardice, the immortals’ deceitful tactics, and the systemic suppression of talent. Even the so-called “Pure Land of the West” engages in blatant bribery. When the venerable arhats Ananda and Kasyapa fail to extort gifts, they deliver counterfeit scriptures, provoking even the gentle Tang Sanzang to exclaim, “This Pure Land still harbors demons who deceive!” The Underworld, meanwhile, operates as a den of corruption and manipulation. Among the nine mortal kingdoms traversed by the pilgrims, most rulers are tyrants whose misrule spawns chaos and monsters. Collectively, these celestial, infernal, and earthly realms symbolize the folly of emperors, the rot within imperial courts, and the moral darkness of the human world.

The demons and monsters in the novel largely allegorize the lawless elites of Wu Cheng’en’s era, embodying predatory forces that oppress the populace. Red Boy, the Sage-Infant King, plunders without restraint; the serpent demon of Tuoluo Village revels in slaughter; the Immortal of Compliant Desires hoards wealth through exploitation; the Golden Carp Spirit seizes power by force—all reflecting the rampant exploitation, oppressive taxation, and tyrannical governance of mid-Ming society. Many of these demons maintain intimate ties with deities or Buddhas. The Roc of Lion-Camel Ridge and the Mouse Spirit of the Bottomless Pit, for instance, symbolize rulers who collude with their underlings to perpetuate chaos, mirroring the collusion between corrupt officials and local despots in Wu’s time. Through these layered allegories, the novel unveils a world where divine and mortal powers alike conspire to perpetuate suffering, offering a scathing indictment of Ming Dynasty sociopolitical decay.

The most distinctive artistic achievement of The Journey to the West lies in its surreal imagination and hyperbolic exaggeration, shattering temporal, spatial, and existential boundaries to forge a phantasmagorical realm where gods, humans, and objects intermingle. Here, settings span celestial palaces, oceanic Dragon Palaces, infernal courts, sacred Buddhist domains, and perilous mountains. Characters are grotesquely shaped, straddling the line between human and monstrous, wielding boundless supernatural powers and shape-shifting abilities. The narratives soar between heavens and earth, churn oceans, vanquish demons, and duel with mystical artifacts, weaving these extraordinary figures, events, and landscapes into a cohesive, harmonious tapestry of fantastical beauty.

This beauty appears "profoundly fantastical" yet resonates as "profoundly real." While the tales brim with bewildering, pulse-pounding marvels, many mirror shadows of reality or distill universal truths about human nature. The resplendent, omnipotent celestial court reflects earthly imperial bureaucracy; its hierarchical, inept immortal officials parallel contemporary courtiers; the annihilation of tyrannical demons allegorizes the eradication of societal evils. By celebrating unfettered freedom to traverse realms, the novel simultaneously embodies aspirations to break constraints and pursue liberation. Through this interplay of the absurd and the authentic, Wu Cheng'en crafts a paradoxical universe where the grotesque illuminates reality, and the impossible unveils profound truths.

Ming Dynasty Critic Xi Bi Zhuren (*Preface to The Chronicles of Loyalty and Heroism**):

"Both The Journey to the West and The Plum in the Golden Vase revel in the fantastical, inundating readers with seductive, extravagant language. Yet, while the wise discern their deeper purpose and artistry, the foolish fixate on their supernatural allure, turning works meant to awaken society into mere entertainment."

Ming Poet Xie Zhaozhe (Wu Zazu):

"The Journey to the West sprawls with wild invention, yet its allegorical core lies in its symbolism: the Monkey embodies the restless mind, the Pig represents unchecked desires. Their initial rebellion—soaring unchecked between heaven and earth—ultimately yields to the Golden Hoop’s restraint, taming the ‘mind-monkey’ into unwavering discipline. This mirrors the Confucian ideal of ‘reining in the heart,’ proving the work far from frivolous."

Ming Fiction Commentator Li Zhuowu (*Li Zhuowu’s Commentary on The Journey to the West**):

"Readers who miss the author’s intent reduce this text to mere whimsy. Unearthing its layers reveals profound truths. Consider the first chapter alone: its brilliance surpasses entire volumes of scripture. The title Tale of Overcoming Calamities suggests liberation through reading. To finish The Journey to the West unenlightened is to betray its purpose."

Qing Scholar Zhang Shushen (*New Interpretations of The Journey to the West**):

"What is The Journey to the West? A marvel of literature, unparalleled in ingenuity—every page astonishes. Hence, it is rightly called a ‘Book of Wonders.’"

Qing Critic Mao Zonggang (On Reading Romance of the Three Kingdoms**):

"Romance of the Three Kingdoms* surpasses The Journey to the West. The latter’s demonic fantasies lack historical grounding, whereas the former chronicles emperors with verifiable truth. Yet The Journey to the West’s virtues are all present in Three Kingdoms."

Qing Scholar Xianzhai Laoren (*Preface to The Scholars**):

"Some deem The Journey to the West a Daoist allegory, citing metaphors like ‘the mind as Buddha’ or ‘the Metal Lord and Wood Mother.’ Yet its mystical vagueness eludes definitive interpretation."

Qing Daoist Scholar Wang Dangyi (The Journey’s Path to Enlightenment):

"Tang Sanzang, born of a golden cicada, embodies purity; his pilgrimage earns him the title ‘Sandalwood Merit Buddha.’ Sun Wukong, vanquisher of evils, becomes the ‘Victorious Fighting Buddha.’ Even Zhu Bajie (‘Altar Purifier’), Sha Wujing (‘Golden-Bodied Arhat’), and the White Dragon Horse (‘Celestial Dragon’) attain roles befitting their deeds. The Buddha’s precise assignments mirror imperial bureaucracy—yet here, hierarchy dissolves into transcendence. This conclusion offers finality, breaking the cycle of rebirth."

Qing Inner Alchemy Master Liu Yiming (*The Original Intent of The Journey to the West**):

"The ‘true scriptures’ sought in The Journey to the West reside within the text itself. By transmitting Tathagata’s teachings, Wu Cheng’en transmits his own. To grasp this tale is to grasp the essence of Buddhist sutras."

Modern Scholar Zheng Zhenduo (History of Chinese Literature):

"Countless tales followed The Tale of Emperor Taizong’s Journey to the Underworld, but Wu’s work stands unrivaled. Sequels like Later Journeys and The Supplement pale in comparison, mere shadows of his genius."

Modern Scholar Hu Shi (*Research on The Journey to the West**):

① "At its core, The Journey to the West is a masterful comic myth—a satire veiled in whimsy, its cynicism plain, demanding no esoteric analysis."

② "Structurally, it surpasses most classical Chinese novels. Its enduring charm lies in humor: unlike sanctimonious paragons, its characters brim with irreverent humanity, securing its place among the world’s greatest mythologies."

Modern Writer Lu Xun (Brief History of Chinese Fiction):

"Though penned by a Confucian scholar, this work springs from playfulness, not dogma. Occasional references to Five Elements theory and a nonsensical sutra catalog in the finale reveal no deep Buddhist or Daoist study. Its syncretic blending of doctrines—Buddha and Laozi coexist, blending spiritual truths with primal energies—allowed all three teachings to claim it as their own."

Modern Literary Scholar Pu Jiangqing (Drafts on Chinese Literary History):

"The Journey to the West champions liberation and equality. Its sharp critique of feudal society, born of lived experience and artistic genius, resonates across ages. Children delight in its adventure; adults uncover its layered wisdom. Herein lies its timelessness."

The Journey to the West established a new genre of mythological chapter-linked novels, blending witty mockery, biting satire, and incisive critique—a combination that profoundly shaped the development of satirical fiction. Regarded as the pinnacle of ancient Chinese romantic literature, it stands as a masterpiece of global Romanticism and a pioneering work of magical realism.

As one of China’s Four Great Classical Novels alongside Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Water Margin, and Dream of the Red Chamber, The Journey to the West has enjoyed enduring popularity since its publication. Countless editions have circulated through the centuries, including six Ming Dynasty printed editions, seven Qing Dynasty editions and manuscripts, and 13 lost versions documented in historical records.

The novel’s impact on later mythological fiction is profound. By the late Ming Dynasty, works like Sequel to the Journey to the West and Later Journey to the West emerged, closely mirroring its narrative framework. Yang Zhihe’s The Story of the Journey to the West and Zhu Dingchen’s Tang Sanzang’s Journey to the West for Deliverance from Calamities further expanded its literary lineage. Notably, Dong Shuo’s late Ming sixteen-chapter The Supplement to the Journey to the West carved its own narrative path with distinctive prose and imaginative plot twists. These derivatives, while varying in originality, collectively attest to the enduring template and creative spark ignited by Wu Cheng’en’s magnum opus.

Provides The Most Comprehensive English Versions Of Chinese Classical Novels And Classic Books Online Reading.

Copyright © 2025 Chinese-Novels.com All Rights Reserved