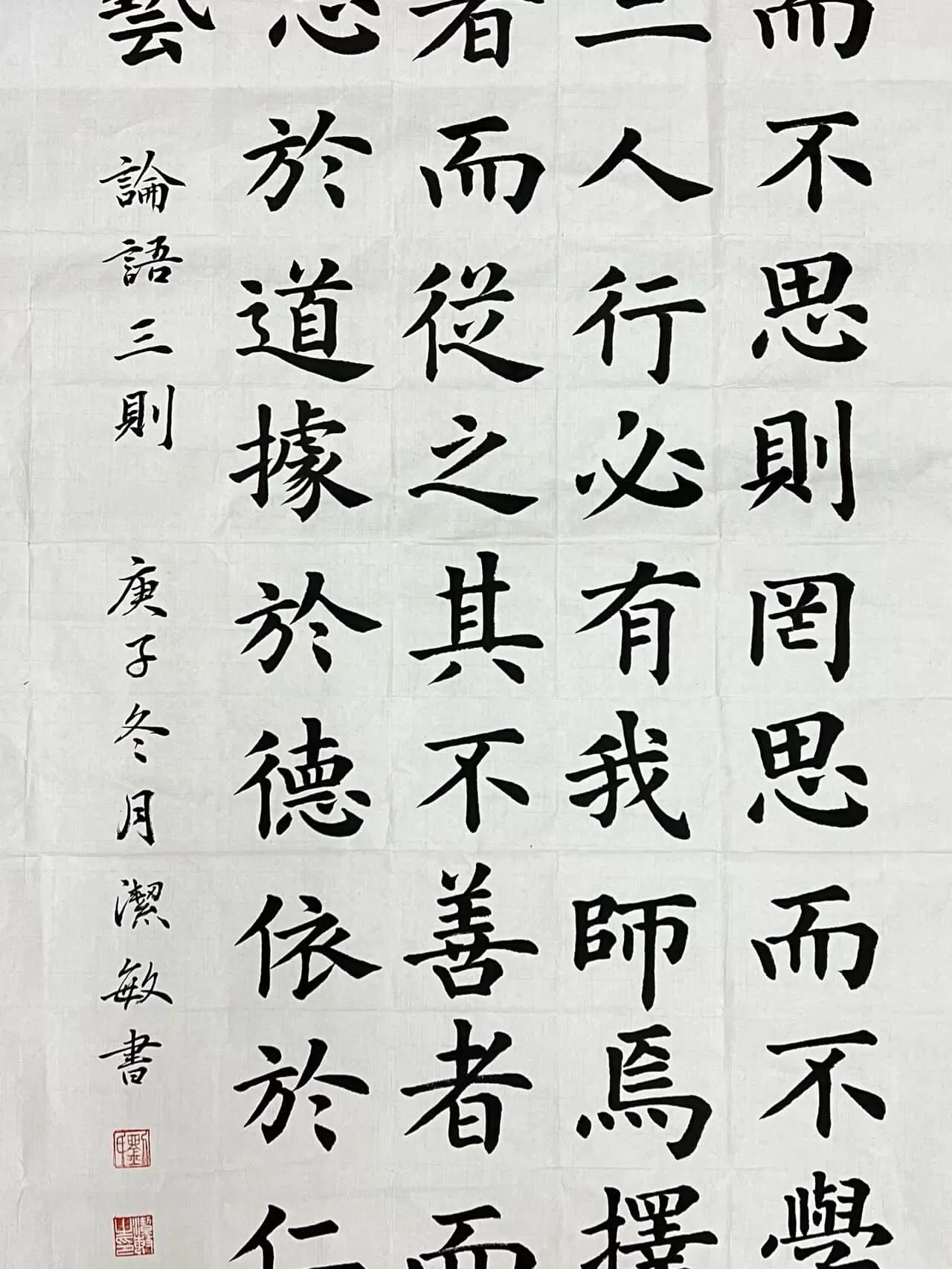

The Analects of Confucius is an aphoristic collection compiled by the disciples of Confucius—a philosopher and educator of the Spring and Autumn Period—and their successors. It records the words and deeds of Confucius and his disciples, finalized during the early Warring States Period.

The text comprises 20 chapters and 492 sections, primarily presented in aphoristic form, supplemented by narrative accounts. It systematically embodies the political doctrines, ethical thoughts, moral concepts, and educational principles of Confucius and the Confucian school. Though predominantly composed of concise sayings, the work features rich meaning beneath its succinct language. Certain passages and dialogues vividly portray characters through simple yet profound exchanges, characterized by an elegant, composed, and subtly nuanced style.

After the Song Dynasty, The Analects of Confucius was enshrined as one of the "Four Books," becoming an official textbook in ancient academies and a mandatory text for imperial civil service examinations.

As a prose collection centered on recorded speech, The Analects primarily preserves the dialogues and interactions between Confucius and his disciples, highlighting his values in governance, aesthetics, moral ethics, and utilitarian philosophy.

The content spans diverse domains such as politics, education, literature, philosophy, and principles for personal conduct. The extant version contains 20 chapters and 492 sections: 444 record conversations between Confucius, his disciples, and contemporaries, while 48 document discussions among Confucius’ followers themselves.

The Analects of Confucius represents the collective wisdom of Confucius’ disciples. Its core content began taking shape during the late Spring and Autumn Period when Confucius lectured at his academy. After his death, his disciples and their successors transmitted his teachings orally across generations, eventually compiling these memorized dialogues and sayings into written form. The term Lun (论) reflects the act of “discussing” or “compiling,” while Yu (语) refers to the recorded “sayings” of Confucius and his disciples. As the Qing scholar Zhao Yi explained: “Yu denotes the sage’s words, while Lun signifies the scholarly discussions among Confucian thinkers.” In essence, Lunyu (论语) means “compiled sayings,” a collection of Confucius’ teachings and interactions. The primary compilers—Zhong Gong, Zi You, Zi Xia, and Zi Gong—initiated the project to preserve their master’s legacy, later collaborating with remaining disciples in Lu and their successors to complete the work.

Qing scholar Cui Shu noted stylistic and titular discrepancies between the first and latter ten chapters of the extant Analects. The first ten chapters, when recording Confucius’ responses to rulers such as Duke Ding and Duke Ai, use the honorific “Confucius replied” (孔子对曰) to emphasize respect for authority. In contrast, answers to ministers are phrased as “The Master said” (子曰), distinguishing hierarchical roles to “clarify social order and guide the people.” However, the latter ten chapters, including Xianjin and Yan Yuan, inconsistently apply “Confucius replied” even in dialogues with ministers. Cui thus speculated that the first ten chapters were compiled by disciples closer to Confucius’ time, adhering to clearer ritual norms, while the latter ten were added later as ministerial power grew, reflecting evolving social dynamics. Further anomalies, such as the frequent use of “Confucius” (孔子) instead of “the Master” (子) in chapters like Jishi and Weizi, or the phrasing “asked Confucius” (问于孔子) in Yanghuo and Yao Yue, suggest these sections were likely interpolated from external sources rather than being original records.

Cui’s observations spurred later scholars to analyze linguistic and titular variations across the text. Some argue that the Analects initially existed as separate chapters, only compiled into a unified text during the Han Dynasty. Tang scholar Lu Deming

As a foundational Confucian classic, The Analects of Confucius encompasses profound and comprehensive ideas, organized into three interconnected yet distinct domains: the ethical-moral domain of ren (humaneness), the sociopolitical domain of li (ritual propriety), and the methodological domain of zhongyong (the doctrine of the mean).

Ren (Humaneness)

Ren represents the supreme moral state rooted in the authenticity of the human heart. This authenticity, when perfected, manifests as goodness, and the synthesis of truth and goodness constitutes ren. Confucius established ren as the ethical core of his philosophy, defining it as the innate capacity for empathy, compassion, and moral integrity. It is through ren that individuals cultivate virtue and harmonize interpersonal relationships.

Li (Ritual Propriety)

Confucius framed li as the sociopolitical expression of ren—a system of norms governing social conduct, hierarchical relationships, and ceremonial practices. Li ensures order and harmony by formalizing roles and responsibilities within families, communities, and governance. It transforms abstract moral ideals (ren) into actionable principles, guiding individuals to act with propriety and respect.

Zhongyong (The Doctrine of the Mean)

As a methodological principle, zhongyong advocates balance, moderation, and adaptability. It rejects extremes, urging individuals to navigate moral and practical challenges with discernment and flexibility. Confucius elevated zhongyong to a systematic approach for ethical decision-making, aligning actions with the equilibrium of cosmic and human order.

Ren stands as the philosophical core of The Analects, unifying its ethical, social, and methodological teachings.

Confucius exemplified pedagogical excellence through differentiated instruction, tailoring his teachings to the unique aptitudes, temperaments, and moral progress of his disciples. His approach reflected both profound psychological insight and unwavering dedication to mentorship.

When asked about ren, Confucius provided distinct answers to different disciples:

To Yan Hui (a deeply cultivated disciple), he outlined ren as a transformative ideal: “Restrain oneself and return to ritual propriety” (Analects 12.1), emphasizing self-discipline and alignment with ethical norms.

To Zhong Gong, he framed ren through relational reciprocity: “Do not impose on others what you yourself do not desire” (Analects 12.2), highlighting empathy and restraint in action.

To Sima Niu, he simplified ren to pragmatic speech ethics: “The humane person hesitates in speech” (Analects 12.3), addressing the disciple’s impulsiveness.

Similarly, Confucius offered contrasting advice to Zilu and Ran You when both inquired whether to act upon learning a moral principle:

To the bold Zilu, he cautioned restraint: “While your father and elder brothers live, how can you act without consulting them?” (Analects 11.22), tempering his impetuosity.

To the cautious Ran You, he urged decisiveness: “Act upon it immediately” (Analects 11.22), encouraging confidence.

These examples reveal Confucius’s nuanced understanding of his disciples’ characters and his commitment to guiding each toward moral refinement. His teachings transcended mere pedagogy, embodying a profound ethical responsibility to nurture virtue in accordance with individual potential.

Though predominantly composed of concise aphorisms, The Analects of Confucius achieves remarkable depth and vividness through its succinct yet profound language. Certain passages, such as the chapter Zi Lu, Zeng Xi, Ran You, and Gongxi Hua Attending Confucius in Seated Discussion (11.26), transcend mere dialogue to form cohesive narratives. This extended episode, structured as a complete vignette, reveals character dynamics and philosophical ideals through nuanced descriptions of expressions, gestures, and interactions, showcasing the text’s literary artistry.

Confucius stands as the central figure of The Analects, with “the Master’s charisma overflowing in his aphorisms” (The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons: In Imitation of the Sage). The text captures not only his dignified demeanor through static portrayals but also his intellectual vitality and moral gravitas through dynamic characterization. Surrounding this central presence, the work vividly sketches the personalities of his disciples:

Zilu’s forthright impulsiveness,

Yan Hui’s gentle wisdom,

Zigong’s sharp eloquence,

Zeng Xi’s unconventional poise.

Each figure emerges distinctly, leaving enduring impressions through minimal yet evocative strokes.

Key stylistic hallmarks of The Analects include:

Conciseness and Depth: A harmonious blend of brevity and profundity, marked by a graceful, subtly nuanced tone that balances moral urgency with contemplative restraint.

Characterization Through Dialogue and Action: Figures come alive not through elaborate description but through revelatory exchanges and gestures, as seen in Confucius’ amused observation of disciples’ contrasting postures (Analects 11.13) or Zilu’s rash interjections.

Accessible Language: Prose rooted in conversational clarity, avoiding ornate phrasing to maintain immediacy and relatability.

This fusion of philosophical weight and literary economy renders The Analects both a foundational ethical text and a timeless work of narrative artistry.

Liu Xiang’s Bielu (Miscellaneous Records), Western Han Dynasty:

“The Lu Analects in twenty chapters consist of virtuous sayings recorded by Confucius’ disciples.”

Ban Gu’s Book of Han: Treatise on Arts and Letters, Eastern Han Dynasty:

“The Analects contains Confucius’ responses to disciples and contemporaries, as well as dialogues among disciples transmitted through the Master. After his death, followers compiled these records into a unified text, hence its name Lunyu (Discourses).”

Wang Chong’s Discourses Weighed: On Correct Interpretation, Eastern Han Dynasty:

“Originally, Confucius’ descendant Kong Anguo taught the text to Fu Qing of Lu, who later rose to Governor of Jing Province. It was then formally titled The Analects.”

Liu Xi’s Explanation of Names: Exegesis of Classical Texts, Eastern Han Dynasty:

“The Analects records Confucius’ conversations with disciples. Lun (Discourses) implies ethical order; yu (sayings) denotes the articulation of ideas.”

Fu Xuan’s Fu Zi, Western Jin Dynasty (quoted in Xiao Tong’s Selections of Refined Literature: Discourse on Destiny):

“After Confucius’ passing, disciples like Zhong Gong compiled his teachings into The Analects.”

Zhao Pu, Northern Song Dynasty (from Luo Dajing’s Crane Forest Jade Dew, Vol. 7):

“All my knowledge derives from this work. With half of it, I aided Emperor Taizu in unifying the realm; with the other half, I shall assist Your Majesty in securing peace.”

Xing Bing’s Commentary on the Analects, Northern Song Dynasty:

“Direct statements are yan (remarks); responses are yu (dialogues). This text harmonizes both, thus earning its title as a compilation of sagely wisdom.”

Zhu Xi’s Classified Conversations, Vol. 105, Southern Song Dynasty:

“The Four Books are the gateway to the Six Classics; the Reflections on Things at Hand is the gateway to the Four Books.”

He Yisun’s Dialogues on the Eleven Classics, Southern Song Dynasty:

“The Analects includes disciples’ notes, Master-disciple exchanges, peer debates, and ministerial discourses—all deliberating moral principles, justifying its name.”

Shao Yichen’s Postscript to the Hall of Ritual Studies, Qing Dynasty:

“Emperor Taizu’s advisor Liu Base initiated civil exams based on the Four Books, a system enduring five centuries.”

Xue Fucheng’s On Imperial Examinations II, Qing Dynasty:

“Standard exams tested essays on the Four Books and Five Classics, altering formats but preserving their doctrinal core.”

Yu Yue’s Spring Hall Essays, Vol. 9, Qing Dynasty:

“In drafting the epitaph for Wen Qin, I noted he mastered the Four Books and Thirteen Classics by age eleven.”

As a cornerstone of Confucian thought, The Analects became a primary source for studying Confucius and early Confucianism after Emperor Wu of Han elevated it to canonical status, declaring it “the axle of the Five Classics and the throat of the Six Arts.” During the Southern Song Dynasty, Zhu Xi grouped it with Great Learning, Doctrine of the Mean, and Mencius into the Four Books, solidifying its supremacy. From the Yuan Dynasty’s Yuanyou era onward, the Four Books formed the basis of imperial civil examinations, a system upheld until the late Qing abolition of the exam system in the 19th century.

Elevated to classical status in the Tang Dynasty, The Analects joined texts like Rites of Zhou and Zuo Commentary in the Thirteen Classics. Northern Song statesman Zhao Pu famously claimed, “Half of The Analects suffices to govern the realm,” underscoring its political and ethical influence.

The text’s inclusion of critiques and debates—such as Confucius’ responses to skeptics—inspired later literary forms like the rhetorical Answering the Guest’s Challenge, which adopted its dialogic structure. Its celebration of perseverance (“knowing the impossible yet striving to achieve it”) affirmed Confucian ideals of moral resolve and self-worth, resonating across millennia as a testament to intellectual and ethical rigor.

Provides The Most Comprehensive English Versions Of Chinese Classical Novels And Classic Books Online Reading.

Copyright © 2025 Chinese-Novels.com All Rights Reserved