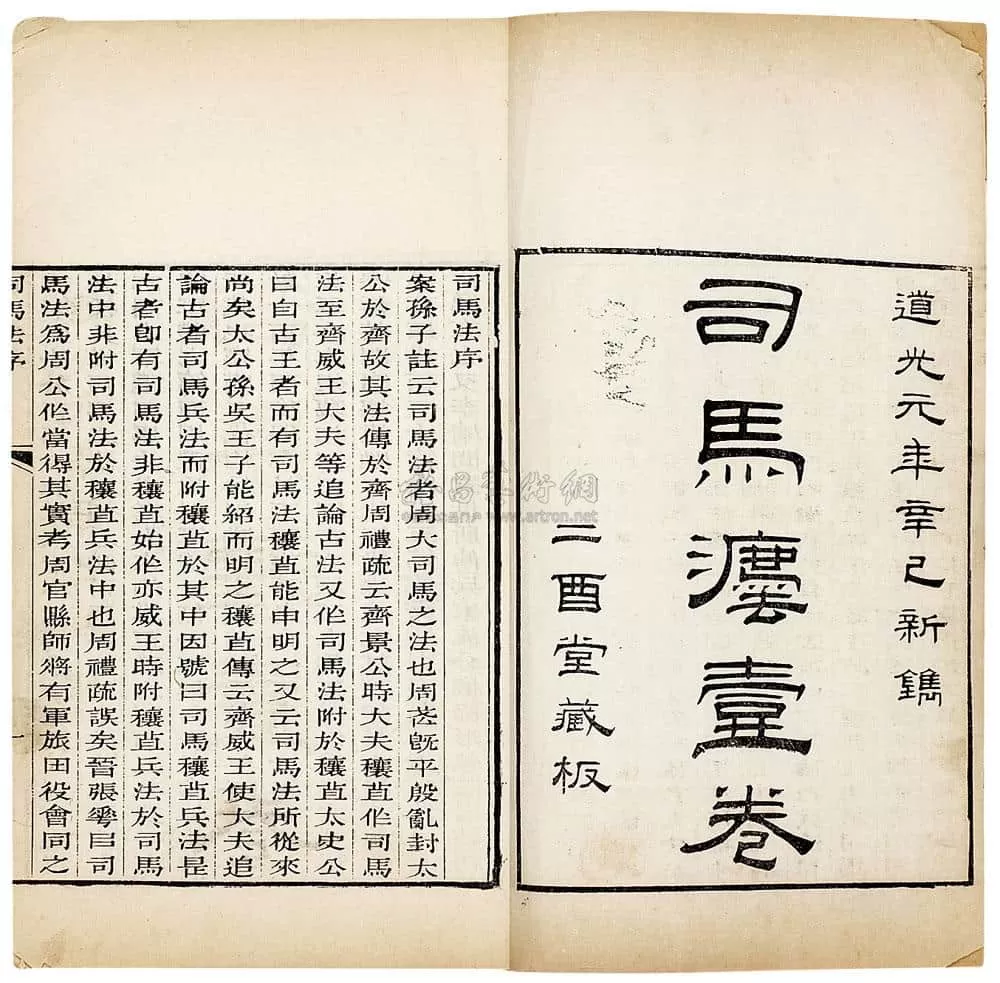

The Military Tactics of Sima first appeared in the "Treatise on Literature" section of the Book of Han (Hanshu·Yiwen Zhi), categorized under rites and referred to as the Military Rites: Sima Fa, comprising 155 chapters. After the Han dynasty, much of the text was lost during its long circulation. By the Tang dynasty, when the Book of Sui·Treatise on Classics and Books (Sui Shu·Jing Ji Zhi) was compiled, only 3 volumes and 5 chapters remained. It was classified under the "Military School" category in the "Masters" section and titled Sima Fa, forming the prototype of the extant 3-volume, 5-chapter version.

According to the Records of the Grand Historian·Biography of Sima Rangju: "King Wei of Qi ordered his scholars to compile ancient military strategies attributed to the Sima (Minister of War) and include the works of Rangju, thus titling it The Military Methods of Sima Rangju." Sima Rangju, a native of Qi during the late Spring and Autumn period, was originally named Tian Rangju. He led successful campaigns against Jin and Yan, and was appointed Grand Sima (Minister of War) by Duke Jing of Qi, earning him the honorific title Sima Rangju.

The Records of the Grand Historian·Postface of the Grand Historian states: "The Military Tactics of Sima has ancient origins. Figures like Taigong, Sun [Wu], Wu [Qi], and Prince [Chengfu] elaborated and clarified its principles." This suggests The Military Tactics of Sima was not authored by a single individual. The original Zhou dynasty text was attributed to Jiang Taigong (Lü Shang). After his death, subsequent scholars revised and expanded it into the version known today.

Legend holds that The Military Tactics of Sima was compiled by successive Sima officials during the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties. As noted in the Tang Li Wendui: "The Zhou Sima Fa originated with Taigong. After his death, the people of Qi preserved his methods. When Duke Huan of Qi sought hegemony, he entrusted Guan Zhong to revive Taigong’s teachings, creating a disciplined army that subdued the feudal lords." Jiang Taigong, the first Sima of the Zhou dynasty, is thus credited with compiling the Zhou-era Sima Fa, building upon Xia and Shang traditions.

The text was highly regarded by military strategists and rulers throughout history. Emperor Wu of Han established military offices and used The Military Tactics of Sima to select officials, granting them ranks equivalent to academicians. Sima Qian praised the work as "vast and profound—even the campaigns of the Three Dynasties could not exhaust its wisdom, nor match its literary excellence." During the Yuanfeng era of the Northern Song dynasty, The Military Tactics of Sima was included among the Seven Military Classics, becoming essential reading for training military officers, selecting generals, and studying warfare.

Due to its antiquity and extensive textual losses, scholars have long debated the authenticity, dating, and authorship of The Military Tactics of Sima. Particularly since the Ming and Qing dynasties, when textual criticism flourished, the work has become one of the most contentious military texts in Chinese history.

Scholars hold varied views on The Military Tactics of Sima. Some argue it is a forgery, while others contend that historical texts such as the Sima Bingfa (Military Methods of Sima), Sima Rangju Bingfa (Military Methods of Sima Rangju), Sima Fa (Methods of Sima), and Junli Sima Fa (Military Rites: Sima Fa) refer to distinct works. Others propose that the extant Sima Fa can be divided into two parts: the first two chapters derive from the ancient Sima Fa, while the latter three belong to the Sima Rangju Bingfa.

Contemporary Chinese scholars generally agree that the current version of The Military Tactics of Sima is not a forgery. They posit that the historical Sima Bingfa, Sima Rangju Bingfa, and Junli Sima Fa are all encompassed within The Military Tactics of Sima. The text is attributed to Sima Rangju and later scholars who expanded upon his teachings. Despite severe textual losses—only 5 of the original 155 chapters survive—the work retains significant military philosophy and historical value.

The Military Tactics of Sima covers a broad range of military topics, addressing nearly every aspect of warfare. It preserves ancient principles of military strategy and governance, including crucial historical details on the rituals of mobilization, weaponry, insignias, rewards and punishments, and military discipline from the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties. Additionally, the text is rich in philosophical thought, emphasizing the interplay between spiritual and material forces in war and the dialectical unity of "lightness" (flexibility) and "heaviness" (decisiveness). It places great importance on human factors, such as morale and leadership, underscoring their critical role in determining the outcome of conflicts.

The Military Tactics of Sima (Methods of Sima) is one of China’s ancient military classics, included among the Seven Military Classics (Wujing Qishu). During the early Warring States period, King Wei of Qi ordered scholars to compile "ancient military methods attributed to the Sima (Minister of War)" and appended the strategies of Sima Rangju, a renowned general of Qi during the Spring and Autumn period. Thus, it is also known as The Military Methods of Sima Rangju (Sima Rangju Bingfa).

The Book of Han·Treatise on Literature (Hanshu·Yiwen Zhi) originally listed the text as Military Rites: Sima Fa (Junli Sima Fa) with 155 chapters, categorized under rites. By the Book of Sui·Treatise on Classics and Books (Sui Shu·Jing Ji Zhi), it was recorded as Sima Fa in 3 volumes, attributed to Sima Rangju and reclassified under the "Military School" category in the "Masters" section. Later historical records and bibliographies largely followed this attribution.

The extant version consists of 3 volumes and 5 chapters:

Benevolence as Foundation (Renben)

The Righteousness of the Son of Heaven (Tianzi zhi Yi)

Establishing Ranks (Dingjue)

Strict Positioning (Yanwei)

Commanding the Multitude (Yongzhong).

Additionally, over 60 fragments of lost text, totaling more than 1,600 characters, survive as quotations in other works. Wei Zheng of the Tang dynasty included excerpts in his Essentials of Governance from the Books (Qunshu Zhiyao). The Song dynasty printed edition from the Seven Military Classics series remains the earliest extant printed version. Over time, numerous annotated editions and reprints have circulated, with no fewer than 40–50 variants documented in historical records.

The Military Tactics of Sima categorizes wars into two types based on their purpose: just and unjust. It defines "just wars" as those aimed at quelling chaos, eliminating harm to the people, punishing tyrants, and supporting the weak. Thus:

"To kill in order to secure peace for the people is permissible."

"To attack another state out of love for one’s own people is permissible."

"To wage war to end war, though tragic, is permissible."

Conversely, wars launched to expand territory, plunder resources, or exploit a nation’s might to oppress smaller states are deemed unjust.

The text advocates that military action must be "rooted in benevolence" (yi ren wei ben). If a ruler violates moral norms, defies virtue, or endangers virtuous leaders, the Son of Heaven (the Zhou monarch) may rally feudal lords to launch a punitive campaign. It outlines nine prohibitions justifying such interventions.

The Military Tactics of Sima emphasizes that wars must prioritize protecting the people’s welfare:

"The way of war: do not act against the seasons, do not burden the people with hardship—this is how we cherish our own people."

"Do not attack during mourning or disasters—this is how we respect their people."

"Avoid mobilizing troops in winter or summer—this is how we show universal care for all."

Regarding enemy territories, it mandates:

"When entering a land of wrongdoers, do not desecrate shrines, ravage farmlands, destroy infrastructure, burn homes, fell forests, or seize livestock, crops, or tools."

"Spare the elderly and children; return them unharmed. Even if encountering able-bodied foes, do not engage unless provoked. If enemies are wounded, provide medical care and send them back."

This distinction between punishing "wrongdoers" and sparing ordinary soldiers, coupled with humane treatment of captives, reflects China’s earliest systematic discourse on wartime ethics, civilian protection, and military discipline.

The Military Tactics of Sima stresses preparedness and prudence:

"Though the world may be at peace, to forget war invites peril."

"Even in times of peace, the Son of Heaven holds grand inspections in spring and autumn. Feudal lords drill troops in spring and train in autumn—this is how they remain vigilant."

It advocates maintaining readiness through biannual military exercises (disguised as seasonal hunts) to ensure the nation remains combat-ready. Yet it warns:

"A state, however powerful, will perish if obsessed with war."

Balancing vigilance with restraint, the text underscores that preparation must never devolve into warmongering. This philosophy of "prepare diligently but wage war reluctantly" remains a cornerstone of its enduring strategic wisdom.

The Military Tactics of Sima asserts that "governing a state prioritizes ritual, while governing an army demands law"—two fundamentally distinct principles. It warns:

"Civil norms do not belong in the military; military discipline does not belong in civil governance."

"Imposing military rigor on civilians erodes public virtue; enforcing civil leniency in the army weakens martial resolve."

The text identifies strict rewards and punishments as the cornerstone of military discipline. It compares the penal systems of the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties, detailing essential principles for military governance:

Codify military laws

Establish binding regulations

Clarify rewards and penalties

These measures ensure order and effectiveness in army management.

The Military Tactics of Sima prescribes an extensive system of military rites (junli), categorized into:

Resource Mobilization: Tax allocation for war, conscription policies.

Military Organization: Chariot and infantry formations, weapon distribution.

Campaign Protocols: Seasonal timing, ancestral rites, temple ceremonies, war justifications, objectives, and chain of command.

Symbolism and Signals: Banners, drums, insignias.

Ceremonies: Oath-taking, victory celebrations, prisoner presentations.

Discipline: Etiquette, prohibitions, maintaining military dignity.

Accountability: Reward systems, punishments, silence orders.

These codified systems reflect its philosophy of "law-based military governance" (yi fa zhi jun), blending ritual traditions with enforceable statutes.

The text outlines five essential qualities for military leaders:

Benevolence (ren)

Righteousness (yi)

Wisdom (zhi)

Courage (yong)

Integrity (xin)

Commanders must embody both moral character and strategic brilliance, leading by example:

"Respect inspires humility; exemplary conduct earns obedience."

Demonstrate humility, decisiveness, accountability, and refusal to shift blame.

By cultivating these virtues, commanders foster armies that are disciplined in conduct, fierce in battle, and unified in purpose. This fusion of ethical leadership and strict legalism became a defining feature of traditional Chinese military thought.

The Military Tactics of Sima's philosophy of warfare is rooted in simple yet profound dialectical thinking. It advocates a holistic approach to war, emphasizing the "Five Considerations" (wu lü):

Harmony with Heaven (timing aligned with natural cycles)

Material Wealth (ample resources and logistics)

Human Unity (cohesion among troops and populace)

Terrain Advantage (strategic use of geography)

Superior Weaponry (well-crafted arms and equipment)

The text stresses meticulous pre-war planning but also demands tactical adaptability during combat. Commanders must:

Conduct thorough reconnaissance to discern shifting enemy conditions.

Tailor tactics to specific adversaries: "Different foes require different strikes."

Analyze contradictions and interdependencies in battlefield dynamics, such as:

Numerical Strength: Superiority vs. inferiority

Momentum: Lightness (flexibility) vs. heaviness (force)

Order: Discipline vs. chaos

Movement: Advance vs. retreat

Challenge: Difficulty vs. ease

Stability: Security vs. peril

Initiative: Leading vs. following

Morale: Vigor vs. fatigue

Composure: Strong calm vs. fragile calm

Fear: Major apprehension vs. minor unease

Through these dialectical relationships, commanders transform weaknesses into strengths, achieving dominance by altering the balance of power.

The text advises penetrating surface appearances to grasp underlying realities:

"Strike when the enemy feigns calm weakness; avoid when they project calm strength."

"Attack when they are weary; evade when they are rested and alert."

"Exploit their profound fears; disregard minor anxieties."

Armaments should be diversified to complement strengths and offset weaknesses:

"Blend long and short, light and heavy, sharp and blunt—each fulfilling its role."

This ensures versatility in close combat, ranged engagements, and siege warfare.

The Military Tactics of Sima highlights the dialectics of rest and exertion:

"Rest breeds complacency; relentless motion breeds exhaustion."

"Prolonged rest erodes resolve, reversing its benefits."

Commanders must balance pauses and action to maintain momentum without overextending forces.

By harmonizing these contradictions, The Military Tactics of Sima crafts a timeless framework for dynamic, responsive warfare, blending philosophical depth with pragmatic tactics.

The Military Tactics of Sima has long been revered by rulers, military strategists, and scholars. Its emphasis on rule of law in military governance and its detailed military statutes provided a foundational framework for subsequent dynasties to codify military codes and regulations. Scholars studying Zhou-era military institutions and annotators of classical texts frequently cited its principles.

From the Song dynasty onward, the text was enshrined as a canonical work for martial examinations, significantly broadening its dissemination. Its influence also extended beyond China, garnering recognition in global military and philosophical discourse.

However, the text’s conservative adherence to antiquity—its rigid idealization of Zhou dynasty models—limited its adaptability to evolving military realities. While its legalist rigor and ethical insights remain valuable, its reluctance to innovate underscores the need for critical engagement with its legacy.

Provides The Most Comprehensive English Versions Of Chinese Classical Novels And Classic Books Online Reading.

Copyright © 2025 Chinese-Novels.com All Rights Reserved