Tao Te Ching, a philosophical work composed by Laozi during the Spring and Autumn period, is also known as De Dao Jing, Dao De Zhen Jing, Laozi, Five Thousand Words, or Laozi's Five Thousand Characters. Written before the divergence of the Hundred Schools of Thought in pre-Qin China, it serves as a foundational text for Taoist philosophy. The original manuscript comprises two parts: the De Jing as the first section and the Dao Jing as the second, without chapter divisions. Later editions reorganized it into 81 chapters, placing the 37-chapter Dao Jing first, followed by the De Jing from chapter 38 onward.

Centered on the philosophical concept of "Dao" (the Way) and "De" (Virtue), the Tao Te Ching explores principles of self-cultivation, governance, warfare, and health preservation, with a primary focus on political philosophy. It advocates the ideal of "internal sagehood and external kingship", presenting profound and expansive ideas that earned it the title "King of All Scriptures." The text's depth and breadth have made it one of the most influential works in Chinese history, profoundly impacting traditional philosophy, science, politics, and religion.

According to UNESCO statistics, the Tao Te Ching is the most widely translated cultural classic after the Bible. Revered as the "Source of Chinese Culture" and "King of All Scriptures," it stands as a timeless testament to humanity's enduring quest for wisdom and harmony.

| Name | Tao Te Ching |

| Author | Laozi |

| Creation Era | Spring and Autumn Period |

| Work alias | The Tao Te Ching, Laozi, Five Thousand Words, Laozi's Five Thousand Writings, and the Tao Te Ching |

| Word count | 5162 words (official version) |

| Category | philosophy |

| Length | Chapter 81 |

The Tao Te Ching (also known as The True Classic of the Way and Virtue, Laozi, Five Thousand Words, or Laozi’s Five Thousand Characters) is a foundational text of ancient Chinese philosophy, composed prior to the emergence of distinct schools of thought during the pre-Qin period. Revered by scholars of its time, it is traditionally attributed to Laozi (Li Er) of the Spring and Autumn period and serves as a cornerstone of Daoist philosophy.

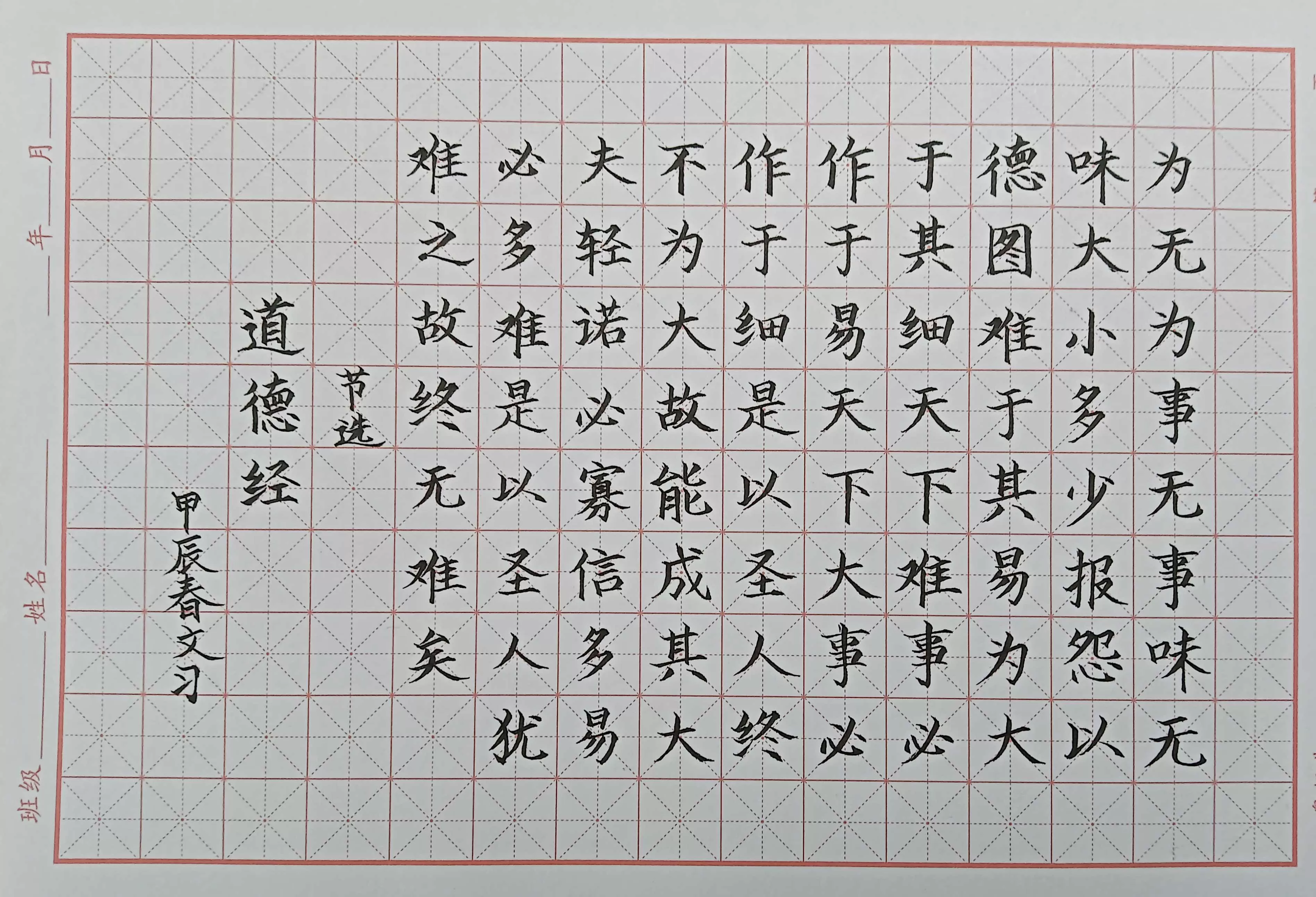

The text is divided into two sections: the De Jing (Classic of Virtue) and the Dao Jing (Classic of the Way). Originally, the De Jing preceded the Dao Jing without chapter divisions. Later editions reorganized the text, placing the Dao Jing (37 chapters) first, followed by the De Jing (Chapters 38–81), totaling 81 chapters. Centered on the philosophical concept of "Dao-De" (the Way and its Virtue), the work explores themes of self-cultivation, governance, military strategy, and health preservation, often emphasizing political philosophy. It embodies the ideal of "sagely wisdom within and kingly governance without," with profound and expansive insights.

The total character count of the Tao Te Ching varies across editions:

Mawangdui Silk Texts: Version A (5,344 characters + 124 repeated characters), Version B (5,342 characters + 124 repeated characters).

Later Editions:

Heshanggong’s Commentary on the Tao Te Ching: 5,201 characters (+94 repeated characters).

Wang Bi’s Commentary on Laozi’s Tao Te Ching: 5,162 characters (+106 repeated characters).

Fu Yi’s Ancient Edition of the Tao Te Ching: 5,450 characters (+106 repeated characters).

The modern standardized edition, based on Wang Bi’s commentary, contains 5,162 characters.

According to historical records, Laozi (Lao Tzu) was a contemplative and erudite thinker with an insatiable thirst for knowledge. As a student under his teacher Shang Rong, he persistently questioned the roots of wisdom, driven by a profound curiosity. To seek answers, he often gazed at the stars and pondered the mysteries of the cosmos, even losing sleep in his quest for understanding. Recognizing the limits of his own knowledge, Shang Rong eventually urged Laozi to pursue advanced studies in the Zhou capital.

Historical texts note: "Laozi traveled to Zhou, where he studied under scholars, entered the Imperial Academy, and immersed himself in astronomy, geography, ethics, cultural artifacts, legal codes, and historical texts. His scholarship flourished, and he was later recommended to serve as an archivist in the Royal Archives—a repository housing the Zhou dynasty’s vast collection of literature and records from across the realm." This role granted Laozi unparalleled access to accumulated knowledge, cementing his reputation as a sage.

Laozi lived during the turbulent Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods (770–221 BCE), an era marked by the decline of the Zhou dynasty and incessant warfare among feudal lords vying for dominance. Witnessing the suffering of the people and the collapse of social order, Laozi—drawing from his position as a Zhou archivist—formulated a series of philosophical principles on governance and social harmony.

The completion of the Tao Te Ching is also attributed to Yin Xi, the Magistrate of Hangu Pass. A scholar of astronomy and ancient texts, Yin Xi recognized Laozi’s wisdom as the sage sought to withdraw from society. Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian recounts: "Laozi, having long observed the decline of Zhou, resolved to depart. At Hangu Pass, Yin Xi implored him: ‘You intend to retreat into seclusion. Compose a treatise for me before you go.’ Thus, Laozi wrote the Five Thousand Characters on the Dao and De, then vanished, his fate unknown." Moved by Yin Xi’s request, Laozi distilled his insights into the Tao Te Ching, synthesizing his observations on the rise and fall of dynasties, the welfare of the people, and the nature of existence. The text’s two sections, totaling five thousand characters, became a timeless cornerstone of Daoist thought.

The central theme of the Tao Te Ching is “The Dao follows nature” (Dao Fa Zi Ran).

This principle encapsulates the essence of Laozi’s thought. “Dao” (the Way), the most abstract and foundational concept in the text, represents the primordial force that generates and governs all things in the cosmos. “De” (Virtue) is the manifestation of the Dao in human ethics and social conduct. While “Dao” and “Fa” (law/norms) share common ground as guiding principles, they differ from Western notions of natural law. Laozi posits that human laws should emulate the Dao’s natural order, functioning through dialectical transformations and the balance of opposites.

Philosophically, the Dao is the mother and origin of all existence. The unity and opposition of Yin and Yang define the essence of all phenomena, while the principle of “reversal at the extreme” (wu ji bi fan) governs cosmic evolution.

Ethically, Laozi’s Dao advocates virtues aligned with nature: simplicity, selflessness, tranquility, humility, softness, yieldingness, and detachment. These qualities reflect harmony with the Dao’s spontaneous flow.

Politically, Laozi promotes “governance through non-action” (wuwei)—ruling without interference, avoiding oppression, and fostering peace. He rejects war and violence, envisioning a society that mirrors the Dao’s natural equilibrium.

These three dimensions—cosmological, ethical, and political—form an interconnected progression in the Tao Te Ching: from the physics of nature to the philosophy of existence, then to moral principles, and finally to a blueprint for ideal governance. The work traces a path from the natural order to ethical virtue, culminating in a vision of societal harmony rooted in the Dao. In essence, it illuminates how the laws of nature guide humanity toward a just and enlightened social order.

The Tao Te Ching spans philosophy, ethics, political science, military strategy, and more, revered by later generations as a sacred text for statecraft, family harmony, self-cultivation, and scholarly pursuit. Its profound impact on Chinese philosophy, science, politics, religion, and culture reflects the worldview and values of ancient China. No school of thought or cultural tradition in China—from pre-Qin philosophers to later intellectual movements—remained untouched by Laozi’s ideas, earning the text the title “King of All Classics” (Wan Jing Zhi Wang). Its influence extends across governance, culture, science, spirituality, and beyond.

According to incomplete Yuan dynasty records, over 3,000 commentaries and studies on the Tao Te Ching had been produced by the 14th century, with no fewer than 1,000 seminal works—a testament to its enduring intellectual legacy.

The text’s dialectical principles, such as the interplay of opposites and cyclical transformation, provided a theoretical framework for internal alchemy (neidan) practices in Daoism, particularly concepts like innate (xiantian) and acquired (houtian) energies, alignment and reversal, and cosmic inversion. Furthermore, its teachings on life’s essence and the ideal human character deeply influenced Daoist views on longevity, spiritual cultivation, and the pursuit of immortal transcendence (xianzhen).

Thus, the Tao Te Ching transcends its role as a philosophical text, shaping both metaphysical thought and practical disciplines, while continuing to inspire seekers of wisdom across time and culture.

Provides The Most Comprehensive English Versions Of Chinese Classical Novels And Classic Books Online Reading.

Copyright © 2025 Chinese-Novels.com All Rights Reserved